Myths I Debunked in Tanzania and Ghana

‘The trouble with Africa,’ says a truck driver with a Cape accent, ‘is that it is so unpredictable. You can never rely on anything going as planned.’

Ironically, this excerpt, plucked from a book titled fittingly ‘The Trouble With Africa‘, turns into something you wouldn’t expect after reading a statement that really says Africa is frustrating.

‘The trouble with Africa, [Vic Ghurs, author] says, is that once it is in your blood, like malaria, it is almost impossible to get rid of. And the trouble with Africa is also the trouble with those of us who settle here: as long as we insist on judging it from a Western perspective, we will be the outsiders — we will be forever baffled by it.’

This quote caught me off guard, and I am beyond happy it found me. I was walking through an art gallery in Arusha, enjoying its peaceful silence and creative energy. In all truth, I was trying to forget about the issues that afflict the city and country, issues that were separated from me by a few inches of concrete and acrylic paint.

Now, I don’t like the blanket term ‘Africa’ to describe all the vibrant and diverse countries within the continent, but in this case the feeling that Ghurs describes in his photo-book is accurate because it’s not a call to generalize Africa. It’s a call to arms for us, as foreigners in their countries, to re-think what we know. The mystical allusion of African countries is like a drug, each one providing its own unique hit of dopamine. And even after visiting all 54 of them, I’m sure the high you’re chasing would not be satisfied.

I led with this idea to challenge the deeply ingrained headspace and preconceived knowledge about the continent. There is no meaningful way to understand the myths you are about to explore unless you approach them without bias. It’s a personal issue I still struggle with, and it’s easy to fall back into that mindset if you’re not careful.

When I switched from health sciences to global development studies in 2015, I took an introductory class titled “Problems of Global Development”. Our professor kicked off the course with an article called “25 Myths About Development”. It caught all of our eyes and was an effective way to engage us in the issues we would be discussing that semester. This post is largely based on that idea — the idea that something as simple as a few controversial concepts can change the way you think about a bigger picture, the idea that snapshot information can be the best way to make you rethink what you know.

And with that, I feel this is the best way to share my experience with the most people. After spending 6 months in Babati, Tanzania, and 1 month in Tema, Ghana, here is a final reflection from a mzungu.

Myth 1: It’s hot everywhere in Africa

Okay, it is hot in many places in Africa, I assume. I had the pleasure of living at a Canadian friendly altitude/temperature of 4,500 feet, drawing a pleasurable climate for my stay in Babati. On the contrary, near Ghana’s capital city of Accra in Tema, you’re situated a mere one meter above sea level and feel the entire wrath of being in such close proximity to the equator.

You might have heard « Africa doesn’t have seasons » which, to the outsider, is a fair assumption. Green and blue are typical colours associated with the temperate continent. In Canada we see shades of white, green, yellow, red, orange, brown, and blue in no particular order throughout the year. But the outsider hasn’t experienced the dry season or the rainy season, at least not how they exist in Tanzania or Ghana. Two extremes, both leaving you longing for its antagonistic counterpart.

I didn’t see rain for three months from June to August in Babati. September in Tema was a rude awakening that, yes, hello, rain still exists. Each wet run in the Ghanaian suburb city, negotiating mud and pot holes felt like an epic scene out of Beyond Limits. Each walk to work, however, forced me to contemplate succumbing to the uninviting pressure of taking a tro-tro or a small-bus-that-carries-more-than-it-can-legally-hold-and-a-goat.

Trying to escape the rain on a tro-tro or dala-dala is only the tip of the iceberg. While we’re clearing off the snow and chipping ice from our windshields, villagers are canoeing through flooded grounds that were once a bustling marketplace of commerce and social interaction. Seasons are real in Tanzania and Ghana, and they are extreme, and they are going to get worse.

Thankfully the farmers of Tanzania have been blessed with rain a generous one-month earlier than expected, a gift from God they often say. It’s a privilege to see the vast, barren savannas grow to life in a lush green glow, but the way calmed rain storms colour the setting sun on a backdrop of the Indian Ocean proves the greatest gift of all.

Myth 2: All African countries are the same

Of course this isn’t true and many of you know it. It is, however, broadly generalized as a homogeneous land mass which is a great disservice and insult to the sheer diversity the continent has to offer.

What does he know? He’s only visited two African countries! Yep, you’re right, I don’t know much. What I do know, though, is that the contrast between East and West Africa is vivid; the way people talk to you, their language, fashion, food, handshakes, cars, clubs, roads, smiles, heritage.

I did my fare share of research prior to embarking on this Tanzanian journey, and I thought my history lessons concluded at the close of my laptop. Little did I know that a whole world of knowledge would be unveiled to me, knowledge and stories that, in hindsight, are suppressed from our Canadian curriculum. Sure, there are time limitations to our schooling, but these facts seem too grand to go unlearned.

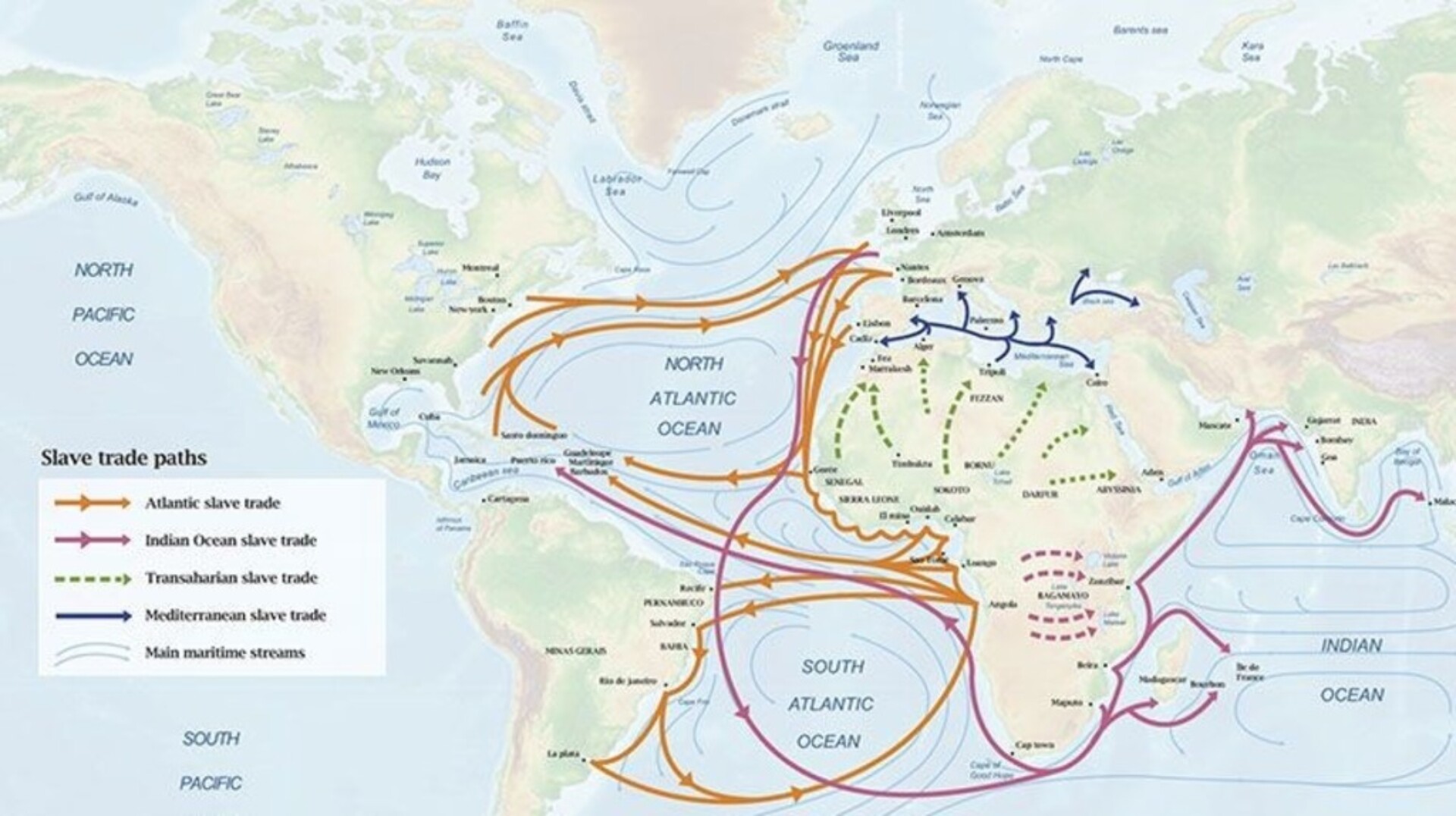

Zanzibar was the East-African slave-trade hub while Cape Coast acted as West Africa’s equivalent. Both « dissipated » well after slavery was abolished by the British Crown in 1838. I visited both of these heritage sights, the former led by major Indian influence, and the latter predominantly by the British. Each exhibit, at their conclusion, made clear that slavery never really ended — a stark realization for some and reality for millions more. A former professor of mine ran my class through an online exercise that calculates how many slaves you employ based on your lifestyle choices. Interested to know your number? Mine’s 27.

I could pay endless homage to the details of how Tanzania and Ghana have developed into largely unique entities, but the bottom line is that these countries have been shaped by the actions of their conquerors; the way people talk to you, their language, food, handshakes, cars, clubs, roads, smiles, their futures, are different.

One day I hope to be able to bring you insight from North and South Africa to complete the picture, but until then, don’t clump the beautiful continent into one idea. If you want to explore this idea more, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie hits the mark with her incredible Ted Talk.

Myth 3: Running is commonplace

I wrote in an earlier reflection that I had seen five runners since my arrival in Tanzania, at the time maybe a month of being in the country. That number grew to be not much bigger than five, maybe 40, 45, including the short 1 month stint in Ghana. Unfortunately it took me until the last week of my stay to discover that there is in fact a small running group in Babati. Oh well.

Tanzania and Ghana are, of course, not well known for their athletics, let alone long distance athletes, but I was still disappointed to be met with so little visual enthusiasm for the sport. After all, I was a clueless runner looking to get immersed in the lifestyle of the most legendary athletes on the planet. Oh, and work a little, too.

There is sharp difference in runner density between cities, towns, and villages — not unlike in Canada where bigger cities draw the most talented athletes. That parallel runs deeper than the running community — cities have a higher population, more funding etc. etc.

To run is to be privileged enough to have the time to do so. As I’ve alluded to in previous posts, free time is a privilege for many in Tanzania and Ghana. Having stayed in areas that qualified only marginally higher than villages, it was a rare sight to see someone running. And when I ran it drew questioning stares, sometimes shrieks of terror (see Mzungu, Mzungu for a more detailed account), largely because I am a white man, but also because people only run when they are late or have someone or something chasing them.

*Takes deep breath* — I know, now, running will never be as important as this work is to me. That realization makes me sad and liberated. Sad because athletics is in my blood and soul, but not in the way I thought it would consume my entire life — the way, instead, that someone might follow results of their past teammates and jump in the occasional road race to chase that distant euphoric personal best feeling. Liberated because, well, put simply running can take over your life. This placement was a crossroads for many aspects of my life — one of the most important being the sport I held so dear for nine years.

Now, that’s not to say it won’t be part of my life because I definitely hope to train and race again. It’s to say the mental and subsequent physical toll required to excel in development work is so overwhelmingly great that you really don’t have a choice. Running and working isn’t a problem. Training, and all the nuances that some of you know accompany that word, and working is a different story. I hope to one day work a job that allows me to comfortably succeed at both.

Myth 4: Time works the same way around the world

What does that mean? Time is a relative concept — now before you jump ship, this isn’t an Interstellar mind-boggling space-time relativity rant — I’m not nearly scientifically inclined enough to tackle that puzzle.

If I tell you ‘Let’s go to the market in 1 hour’ you’ll think ‘okay, I have to be ready to leave in 1 hour’. Makes sense right? Yes, it does. However, tens of thousands of kilometers away from Canada it’s not the same. If I were to say the same statement to a local, it would imply ‘okay, I have to start thinking about being ready in 1 hour, and then I’ll be ready in 2 or 3 hours’ which is quite normalized across Tanzania and Ghana.

You can imagine all its implications — ordering food, organizing trainings, having meetings — you kind of adjust, but also hope you don’t because when you return to wherever you’re from you want to retain that sense of punctuality.

Not only is it a cultural norm to live a ‘pole pole’ (pronounced powlay powlay) or slow slow life but the communication barrier makes scheduling even more of a challenge. You might say one thing, but the person you’re organizing with understands another.

This is an issue across the world — poor communication practices are not limited to Tanzania or Ghana, we face this problem in Canada as well. To help stem the issue, part of the training I delivered with MVIWATA, my partner organization, was how to have effective communication with your peers.

If you were to ask me the biggest takeaways I gained from this experience I would answer with renewed (sometimes frustrating re: The Trouble With Africa) perspectives on cross-cultural communication and patience.

Myth 5: Government funds go to NGOs

The process by which money from your pocket reaches a person on the ground in a developing country always confounded me. How does that work? Is it an e-transfer? Do they get cash mailed to them? Does someone hand them money and they go to the store and buy maize with it? Does it reach them at all? Uniterra Tanzania and Ghana helped me uncover the answers to these questions.

It’s not exactly a myth, but there is more than meets the eye. Certain programs, like Uniterra, ask volunteers to contribute a small sum, and the rest is subsidized by the Canadian government. Our contributions as volunteers cover basic necessities like flights, visas, and vaccinations.

A large part of your donation is probably going to administrative costs. That’s not a bad thing, though. It’s kind of a trade off — while the money goes to the organizations, people are coming from all over the world to volunteer freely. The volunteers will likely (if the organization supports them) get free accommodation and a modest living allowance. Of course there are thousands of different organizations, not all, in fact very few, have volunteer programs. You might be paying a workers salary or buying equipment for a farming start-up. The possibilities are endless.

But by extension, the money a contract volunteer or salaried worker receives reaches a number of different people: I pay Fadhili, my bajaji driver, to take me to work every day; I go to the same woman at the local market twice a week; I go out for dinner to a few local restaurants; I pay Adamu, a local guide, to take me hiking; I buy beer at Tina’s bar; I pay Halima, my housekeeper, to clean and do laundry. This money, mostly from the Canadian government, is going directly to the hands of people I interact with on a daily or weekly basis.

Myth 6: International aid doesn’t work

This is the never ending struggle development practitioners navigate. Am I making a difference? Do these people even need me? They’re questions you ponder frequently and often to no ends. But getting hung up on deep thoughts forces you to miss the point.

We can’t do much, hell, as I posted on this blog before I left, Uniterra sends students abroad knowing of their absent experience. That’s the point, though. Just as any company or corporation hires students straight out of school, they aren’t looking for someone to positively transform their business (although I’m sure that would be welcome), but rather inject new energy and perspective into situations often deadlocked by stale knowledge. Volunteers have the unique opportunity to be a part of that process with various grassroots NGOs around the world.

Of course there are problems with the industry, if there weren’t then we would all be out of a job. Infrastructure, time, knowledge, disease, addiction — all limiting factors in international development. Death is very commonplace in Tanzania, as I’m sure it is elsewhere in Africa, and as a result of having large families, frequent funerals take way from work and productivity.

Whether you like it or not, one important part of working in a developing country is understanding how to work within the local system outside of what you know and what you’re used to. This means appreciating little victories like making an elder laugh at an activity of self-discovery for their conflict management style, or a child smile as you wave to them, or fellow volunteers getting that Aha! moment.

One of the biggest ideas I’ve struggled with over the last few years is thinking that there are only a handful of ways to help people. In my studies we were implicitly taught to loath other programs because to approach things ‘differently’ from a non-institutional perspective, as we did, was the ‘right’ way. But how do you do that within the confines of an institution so established such as the University of Western Ontario?

The bottom line is that no matter what you’re doing, no matter where you are it is helping someone, somewhere — whether that be your colleague de-stressing so they can go home and enjoy their family, or a child in rural Somalia get a meal that day, and everything in between. My error in judgement was that if you weren’t working directly with the people you sought to help then it didn’t count. Our actions, however, always have an impact on someone.

These are the big ideas I’ve come across on this short journey away from home, and I’ve found it meaningful to reflect on them as I return to Canada in one week.