Success story

When Women Producers Lead the Way

Volunteer in Parakou, Benin, supporting the National Federation of Shea Nut and Shea Butter Producers. I am doing a six-month mandate as a Commercial Marketing Advisor.

My Arrival in Parakou

When I arrived in Parakou after an eight-hour drive from Cotonou, I was welcomed by a federation that represents far more than a professional association: it brings together over 70,000 shea nut and shea butter producers across five regions of Benin. From the very first hours, I sensed how deeply this organization is rooted in women’s collective strength—through their solidarity, expertise, and a shared determination to advance a sector essential to their livelihoods and economic autonomy.

When I arrived in Parakou after an eight-hour drive from Cotonou, I was welcomed by a federation that represents far more than a professional association: it brings together over 70,000 shea nut and shea butter producers across five regions of Benin. From the very first hours, I sensed how deeply this organization is rooted in women’s collective strength—through their solidarity, expertise, and a shared determination to advance a sector essential to their livelihoods and economic autonomy.

The President, Ms. Mamadou Djafou, greeted me with a warmth I will never forget. She introduced me to daily life with simplicity: impromptu meals, conversations over plates of pounded yam, meetings held despite the oppressive heat or power outages. I had to adapt quickly—to fans that suddenly stopped working, days exceeding 40°C, and an open work environment where privacy was nonexistent. Yet the team’s welcome, trust, and humor made every adjustment easier. Very soon, I felt able to contribute, ask questions, and propose ideas.

It was within this context that a major shock occurred: the announcement of the suspension of significant funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. government agency responsible for international development assistance and humanitarian aid. This decision deeply affected the federation, which relied partly on this support to provide training, assist cooperatives, and strengthen the value chain. Professionally, it was a crucial challenge: how could we maintain the organization’s mission, stabilize operations, and continue supporting tens of thousands of women in such an uncertain environment?

My mandate then took a decisive turn. It became clear that strengthening the federation’s strategic autonomy was essential. Together with the team, we embarked on complex work: developing a five-year business plan—an essential tool to guide decision-making, structure activities, and, above all, support the mobilization of new funding.

This process required deep immersion. I needed to understand the producers’ diverse regional realities:

- differences in shea processing methods;

- variations in marketing approaches;

- logistical challenges related to distance and transportation;

- the impact of domestic workloads on women’s availability;

- diverse collective organizational strategies;

- barriers to organic certification;

- and climatic conditions affecting harvests.

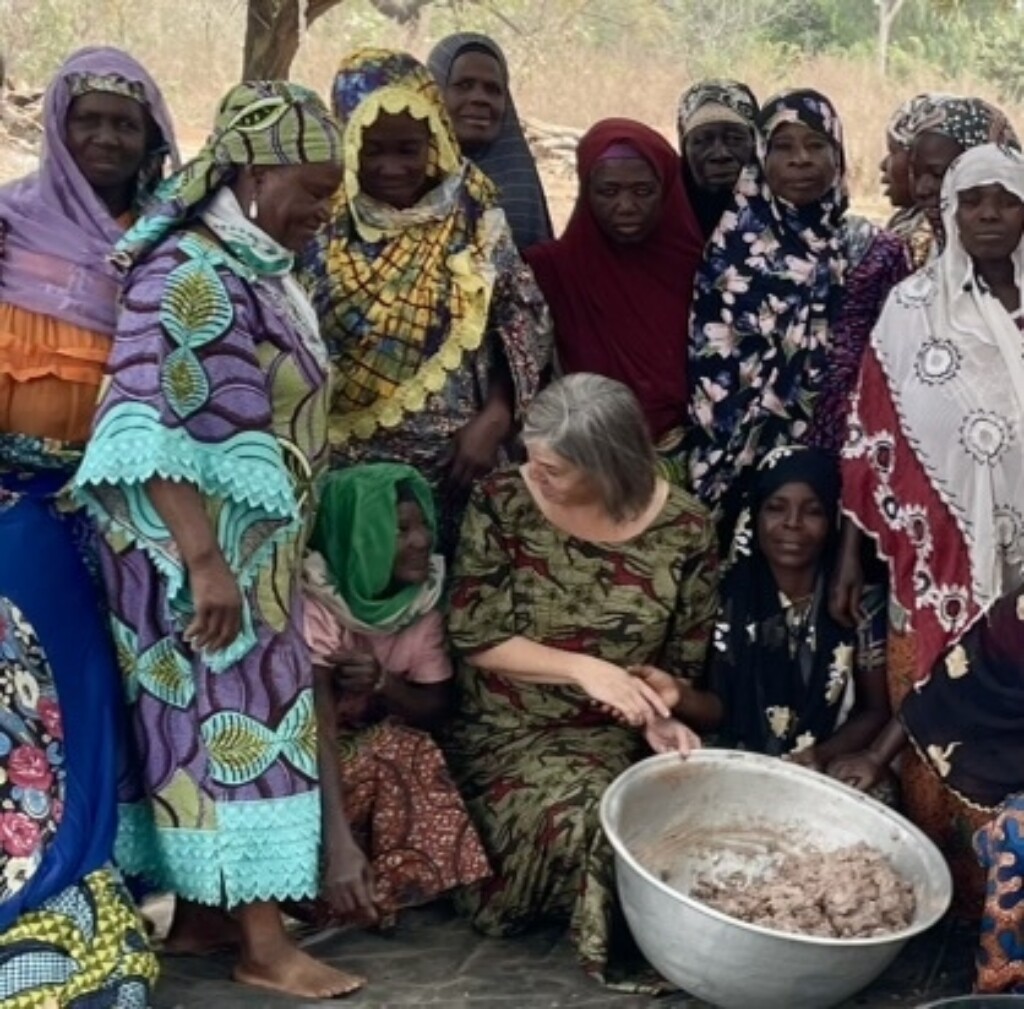

To do this, I accompanied the President on several field missions. Some cooperatives even offered complete demonstrations of shea processing so that I could understand every step and identify potential improvements. Producers showed me how they assess roasting “by sound,” organize collective work, and manage harvest and processing periods alongside family responsibilities.

These moments were invaluable. They revealed immense local expertise—often absent from official documents, but absolutely essential for designing a realistic and sustainable strategic plan. I learned more through these informal exchanges than from any report.

One of the greatest professional challenges was ensuring representativeness. How could we develop a national strategy when realities varied so widely? I therefore multiplied validation steps—with the internal team, board members, and the producers themselves. I rephrased, returned for clarification, and adjusted. I wanted each recommendation to reflect their vision faithfully. The business plan had to belong to them: it needed to extend their ambitions, not impose an external projection.

Over the months, a profound transformation took place. I saw board members grow in confidence. They spoke up more often, dared to ask questions, debated among themselves, and requested clarifications. During a congress, one moment deeply moved me: Ms. Djafou and Awaou, a young producer and board member, addressed institutional representatives, pointing out that discussions about the shea sector often lack the presence of women themselves. Their message was clear: “If we talk about shea, we must speak with those who produce it.” They also emphasized that during a three-day conference, they were the only producers invited to the main stage. Their voices resonated. Their leadership emerged powerfully.

That moment encapsulated the impact of the mandate: not only was a business plan being built, but a space for women’s leadership and governance was being strengthened.

For the federation, the impact has been significant:

- a 60-page co-created business plan, realistic and tailored to local realities;

- increased capacity to advocate for priorities with donors and partners;

- strengthened women’s leadership within decision-making bodies;

- a more inclusive dynamic within the board of directors.

For me, the mandate was both a professional and personal transformation. I learned to work amid uncertainty, to navigate organizational systems weakened by external decisions, and to engage with rich and sometimes challenging cultural contexts. Above all, I learned to slow down—to understand that trust is built over time, through simple gestures and consistent presence. I learned to recognize that producers’ expertise is the cornerstone of any meaningful strategic process.

This experience reaffirmed a fundamental truth: sustainable change is not achieved for women, but with them. In northern Benin, it was the producers who charted the path. Together, we transformed a period of uncertainty into a strategic stepping-stone, and I had the privilege of learning alongside them, guided by their stories, decisions, and leadership.

Our partners

Thank you to our financial and implementation partners, without whom this project would not be possible. CECI's volunteer cooperation program is carried out in partnership with the Government of Canada.